Abstract

This article asks why public officials perceive some interest groups as influential for policy outcomes. Theoretically, we rely on resource exchange and behavioral approaches. Perceived influence of interest groups does not only follow from the policy capacities they bring to the table; it also relates to the extent to which public officials consider groups as policy insiders. Both effects are assumed to be conditional on advocacy salience, i.e., the number of stakeholders mobilized in each legislative proposal. We rely on a new dataset of 103 prominent interest groups involved in 28 legislative proposals passed between 2015 and 2016 at the European Union level. Our findings show that interest groups associated with high analytical and political capacities are perceived as more influential for final policy outcomes than other groups with less policy capacities. Yet, in policy issues with high advocacy salience, interest groups characterized by higher ‘insiderness’ are perceived as more influential among public officials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Public officials regularly interact and consult with interest groups to come up with effective, legitimate, and implementable public policies. During these interactions, some groups are perceived as more influential than others on the outcome of the policy issue under discussion. Although research has increasingly addressed the issue of interest group influence (e.g., Binderkrantz et al., 2014; Dür et al., 2015; Klüver, 2011; Mahoney, 2007; Tallberg et al., 2018), the elusiveness of the concept and the difficulties linked to its empirical observation hamper the ability to accumulate knowledge on this topic. However, knowing which interest groups are more influential and why remains a core question in public policy studies (Weible et al., 2011). To contribute to this field, this article focuses on public officials in charge of developing legislative dossiers and examines the following research question: why do public officials perceive interest groups as influential?

As actors directly involved in decision-making processes, public officials have one of the most accurate views of how power is allocated among actors (Fischer & Sciarini, 2015, p. 60). Although few studies take public officials’ perspectives when examining interest group influence (but see Dür et al., 2015), their view is key to further comprehend which actors have an important role in the development of public policies. As succinctly phrased by Heaney (2014, p. 67), ‘if an actor is believed to be influential [by public officials], then its actions (or inactions) might be viewed as likely to prompt policy change (or stasis); if the actor supports a proposed policy, that policy might have a greater chance of moving forward; if the actor fails to support a proposed policy, then that policy might have a lesser chance of success.’ Despite its importance for policy processes, we still have limited understanding of why public officials perceive certain groups more influential than others.

Our empirical examination of interest groups’ influence is focused on a subset of groups that are regarded as key by public officials working on certain policy issues. These prominent groups are on the top of public officials’ mind when working on specific policy issues (Halpin & Fraussen, 2017). Despite being considered by public officials as relevant organizations for the policy issue under discussion, prominent groups are not equally influential in public policy processes (Grossmann, 2012), which calls for research examining the factors that shape their ability to influence policy processes. In other words, this article improves our understanding of policy processes by examining which voices are more likely to be perceived as influential by public officials, and which factors shape their assessment. The short-cuts public officials apply to assess the relevance of key groups, and the resulting inequalities or biases among prominent interest groups, have important implications for the quality of public governance.

We rely on the assumption that the perceived influence of (prominent) interest groups follows from possessing specific capacities which are believed to facilitate decision-making processes among public officials (Lowery, 2013, p. 4). In this regard, the distinction made between the exercise of influence and the bases of power, or the capacities that enable interest groups to exercise this influence, is of particular relevance (Simon, 1997). More specifically, the article combines two approaches that enable us to examine different bases of power and their relationship with perceived influence. First, we build on a resource exchange approach theorizing that the policy capacities of groups, i.e., ‘the set of skills and resources—or competences and capabilities—necessary to perform policy functions’ (Wu et al., 2015), are crucial for their influential role in public-policy making (Bouwen, 2002; Braun, 2012; Daugbjerg et al., 2018; Eising, 2007). Second, we theorize the extent to which a group is considered as a policy insider by public officials will affect the perceived level of influence on policy outcomes. Policy insiderness is conceptualized here as the extent to which interest groups are regular and familiar partners with public officials and whether they are considered as one of the few alternatives on a policy issue. The idea of policy insider is related to the concept ‘policy community’ (Jordan & Maloney, 1997) and considers whether the privileged position of interest groups in certain policy domains, and their level of ‘insiderness’, affects their ability to shape the content of legislative proposals (Bunea, 2017; Fraussen et al., 2015). In summary, the core assumption is that some interest groups will be perceived as more influential than others based on their possession of policy capacities and their degree of policy insiderness.

To provide a complete answer to our research question, we account for variation in the advocacy salience of the policy issue (i.e., the number of stakeholders that mobilize in the policy issue under discussion). Aligned with most recent developments in the literature, we acknowledge that (perceived) influence is a contingent phenomenon (Bernhagen et al., 2015; Beyers et al., 2018; Junk, 2019; Klüver, 2011; Klüver et al., 2015; Lowery & Gray, 2004; Stevens & De Bruycker, 2020). When a policy issue attracts a lot of attention among the lobbying community, public officials are likely to be more cautious and adapt their decision-making process to avoid reputational issues and ensure the successful approval and implementation of the legislation (Junk, 2019). Accordingly, advocacy salience is a crucial moderating variable that may alter the needs of public officials because they have to adapt and deal with the outside pressures related to the policy issue under discussion. More specifically, the policy capacities demanded by public officials and their reliance on policy insiders is likely to change when stakeholders mobilize in greater numbers (Beyers et al., 2018).

Empirically, the article relies on quantitative information provided by top public officials of the European Commission leading 28 EU legislative proposals passed between 2015 and 2016. Our analyses use quantitative data on 103 prominent interest groups mentioned by the interviewed public officials. Our findings show that the groups that are perceived as more influential for the final policy outcome are those that are associated with higher analytical and political capacities. When accounting for the moderating role of advocacy salience, we find that policy insiderness is positively related to perceived influence, particularly when advocacy salience is high.

Explaining variation in perceived influence among interest groups

In this section, we develop a theoretical approach to explain why some interest groups are perceived as more influential by public officials for policy outcomes than others. We do so by complementing the commonly used resource exchange framework with a behavioral approach to more fully account for public officials’ perceptions. Last, we hypothesize how the advocacy salience of issues under discussion affects such patterns of perceived influence.

Policy capacities and perceived influence

Following an exchange approach (Bouwen, 2002; Braun, 2012; Eising, 2007; Flöthe, 2019), we argue that to thoroughly develop policy proposals in a context of imperfect knowledge, public officials will reach out to interest groups with different types of policy capacities (such as valuable knowledge, technical expertise or political skills) that reinforce the legitimacy and effectiveness of future legislations (James & Christopoulos, 2018). Consequently, when public officials consider some groups as having more policy capacities to supply relevant policy input, these groups are likely to be perceived as more influential in public policy (Daugbjerg, 2022; Daugbjerg et al., 2018). We assume that public officials value groups for their ability to provide technical knowledge related to the content of policy issues, and for their capacity to provide the position of key constituencies and the political consequences of policy alternatives. In other words, we distinguish between analytical and political capacities (Bouwen, 2002, 2004; De Bruycker, 2016; Flöthe, 2019; Hall & Deardorff, 2006; Truman, 1951), which help public officials to develop technically thorough and legitimate public policies (Daugbjerg et al., 2018).

Analytical capacities relate to the abilities to gather and offer policy expertise and technical knowledge required to understand the sector and the specific content of policy issues under debate (Daugbjerg et al., 2018). In order to develop consistent and implementable legislations, public officials are in need of quality policy input such as technical expertise as well as information about the legal aspects and the economic or societal impact of different policy measures (De Bruycker, 2016; Wright, 1996, p. 82). Therefore public officials are likely to identify groups that possess and supply analytical capacities as more influential, because their policy input is expected to facilitate the development of legislations (Bernhagen et al., 2015).

Public officials are also in need of political capacities, as these clarify whether and to what extent legislative initiatives have the necessary political support and are accepted by constituencies that are affected and targeted by them (Albareda, 2018; Maloney et al., 1994). Ensuring that legislation is aligned with the political interests of those that will be affected is expected to foster (input) legitimacy of the policy process (Klüver, 2011), and may have a positive impact on future compliance (Daugbjerg, 2022). In that regard, when groups are seen as possessing political capacities, they are likely to be identified as more influential for the policy outcome.

H1a

Interest groups with more analytical capacities are perceived as more influential by public officials than those with less analytical capacities.

H1b

Interest groups with more political capacities are perceived as more influential by public officials than those with less political capacities.

Policy insiderness and perceived influence

Public officials' interactions with interest groups are not only shaped by the amount of policy capacities that interest groups possess, behavioral dynamics are also at play (Baumgartner & Jones, 2015; Braun, 2013; Simon, 1997). Take for instance the National Farmers’ Union of Scotland, which 'has been stripped of internal independent research capacity, has a low number of expert staff as well as a small and shrinking resource base. Yet it is the dominant farm group in Scotland' (Halpin, 2014, p. 180). In other words, irrespective of declining or low analytical and political capacities, groups might still be considered key actors for other reasons. More specifically, policymakers' behavioral dynamics (i.e., routines, heuristics, and prior attitudes) make them rely on a subset of familiar and trustful actors: policy insiders.

Public officials rely on a specific repertoire of encoded solutions and routinized behaviors (Jones, 2003, p. 400), particularly when selecting and interacting with interest groups. Here, the ability of groups to be(come) regular or familiar partners, and to be considered by public officials as one of the few alternatives on a policy issue, is related with the idea of being a policy insider. According to Jordan and Maloney (1997, p. 560) public officials look for advice ‘among regular, reliable, and knowledgeable sources.’ Policy insiders are therefore interest groups that have a privileged position in policymaking processes, particularly in terms of frequent access with public officials (Bunea, 2017; Fraussen et al., 2015).

Thanks to their frequent access to public officials, policy insiders enjoy a central position in the decision-making network which makes them gain control over ‘flows of resources or information’ (Fischer & Sciarini, 2015). Consequently, policy insiders are likely to have ‘a more experienced understanding of policy dynamics and the institutional setting’ (Bunea, 2017), which is also conducive to power (Fischer & Sciarini, 2015). Because of this, public officials are likely to perceive groups with higher levels of insiderness as more influential because they trust them, likely reducing their discomfort and cognitive dissonance (Hall & Deardorff, 2006, p. 76).

Importantly, policy insiderness and perceived influence are conceptually and empirically distinct (Tallberg et al., 2018). The former relates to having a privileged status among public officials, but having this status does not guarantee influence in every policy processes. Not all policy insiders share similar preferences, nor do their preferences always align with the viewpoints of public officials. In that regard, this expectation is not based on the idea of sharing core beliefs and aligned preferences (Sabatier, 1988), but on the idea of trust and a lasting collaboration (Braun, 2013; Bunea, 2017). In sum, the extent to which some interest groups are perceived as influential for final policy outcomes will be affected by the degree of insiderness that interest groups have among public officials (Scott, 2001; Simon, 1997).

H2

The higher the degree of policy insiderness that interest groups have among public officials, the higher the perceived level of influence they will have.

Perceived influence in context: The moderating role of advocacy salience

Empirical studies have shown the importance of context when assessing the level of access and influence of these actors (Dür et al., 2015; Grömping & Halpin, 2021; Klüver, 2011; Mahoney, 2007; Stevens & De Bruycker, 2020). In this respect, we argue that advocacy salience, defined as the number of stakeholders mobilized on a particular policy issue, is a crucial conditioning factor to assess perceived influence of interest groups (Beyers et al., 2018; Junk, 2019). Unlike other proxies for salience, advocacy salience is an independent measure not based on perceptions of public officials or interest groups (Beyers et al., 2018), providing us with a valid reflection of how the interest group communities perceive the policy issue under debate. Previous research has demonstrated that advocacy salience can vary considerably from issue to issue, leading from issues on which only very few stakeholders mobilize, to ‘bandwagon’ issues that attract a very large community of groups (e.g., Halpin, 2011). Our main assumption is that the policy capacities required by public officials, as well as the extent to which they value ‘insiderness’, will vary depending on the advocacy saliency of the issue under discussion.

Firstly, the demand for analytical capacities is expected to remain constant across the different levels of advocacy salience. Regardless of the number of stakeholders mobilized, public officials will be in need of technical and expert resources to develop sound and implementable legislations. De Bruycker (2016) empirically shows that salient policy issues do not generate substantial differences in the extent to which interest groups supply technical information. In a similar vein, we expect public officials to process and judge the analytical capacities of interest groups independently from the advocacy salience in the issue. Consequently, interest groups that are seen as possessing analytical capacities will be perceived as influential in policy issues with either low or high advocacy salience.

Secondly, public officials are more concerned about obtaining political capacities when an issue mobilizes many stakeholders. As shown by Willems (2020), groups that provide broad societal support (i.e., political capacities) are more likely to gain access to advisory councils in highly politicized policy domains. Highly salient issues require input legitimacy that can be obtained through political capacities (De Bruycker, 2016), as this can facilitate the acceptance of the final outcome among the constituency that will be directly affected and the general public (Maloney et al., 1994). As noted by Junk (2019, p. 661), when an issue is salient in the lobbying community, 'policy makers will be more wary of political repercussions of policy outcomes that lack broad support'. Consequently, interest groups that are seen as possessing more political capacities will be perceived as more influential for the final policy outcome when advocacy salience is high.

Thirdly, regarding the interaction between advocacy salience and policy insiderness, we expect that in highly salient issues, public officials are overloaded by information, making their attention a scarce resource (Simon, 1997). In issues with high advocacy salience, public officials are ‘bombarded with diverse information from many different sources, with varying reliabilities. Policymakers, as boundedly rational decision makers with human cognitive constraints, focus on some of this information and ignore most of it’ (Jones & Baumgartner, 2012, p. 7). As a consequence, as policy issues receive more attention, public officials need to be more selective (Jones & Baumgartner, 2005), and thus, they are expected to rely more heavily on their routinized interaction with policy insiders, whom they can trust due to previous relations. Groups that are part of public officials' policy communities (Jordan & Maloney, 1997) provide strong and stable guides of behavior, particularly in highly salient policy issues (Jones & Baumgartner, 2012). Therefore, the perceived influence of policy insiders is expected to be higher in highly salient issues, as public officials will prioritize interactions with stakeholders they already know and trust.

H3a

The effect of analytical capacities on the perceived influence of interest groups does not change when advocacy salience is high.

H3b

The effect of political capacities on the perceived influence of interest groups increases when advocacy salience is high.

H3c

The effect of policy insiderness on the perceived influence of interest groups increases when advocacy salience is high.

Method

The case: public officials of the European Commission

To study why public officials perceive some interest groups as influential, we focus on the perspective of public officials of the European Commission leading a set of legislative proposals. We center on Commission officials formulating and developing legislative proposals with a regulatory component, which is the dominant legislative output at the EU level (Majone, 1999). This renders a relevant case to assess how policy capacities of interest groups together with the behavioral dynamics of public officials shape the perceived influence of interest groups (see also, Lodge, 2008; Versluis, 2019).Footnote 1

Importantly, the European Commission is the institutional venue where policy-making processes are initiated within the EU. During the formative stage—before the Commission issues a legislative proposal that will be subsequently discussed at the European Parliament and the Council—public officials within the Commission consult and interact with interest groups so as to obtain political and expert information about the content of the legislation. Commission officials, as most bureaucrats in western democracies, require and seek input from external stakeholders (for a discussion see Fraussen & Halpin, 2020). In fact, the Commission's need for interest group policy capacities may be particularly high because of its limited staff when compared to national governments (Bouwen, 2009; European Commission, 2018; Mclaughlin et al., 1993).

The Commission’s intrinsic need for technical and political information that legitimizes its activities (Rittberger, 2005) makes public officials working in this institution dependent on both analytical and political capacities from interest groups (Klüver, 2011). Moreover, as in many other national and supranational polities, public officials of the Commission are also constrained by time and resources, which might lead to decision-making short-cuts, bias in selecting information, simplification and distortion in comprehending information, as well as cognitive and emotional identification when solving problems (Jones & Baumgartner, 2005, p. 16).

Sampling

Our sample of legislative proposals is based on a three-step process. Firstly, we selected all legislative output passed between 2015 and 2016 and that followed the ordinary legislative procedure—the standard decision-making process used for adopting EU legislation, covering the vast majority of areas of the EU (European Union, 2012). In total, we downloaded 127 legislations through Euro-Lex. Subsequently, we excluded cases that were exclusively distributional in nature (N = 10), centered on EU agency functioning or EU internal matters (N = 8), could not be classified in any of the six policy domains of interest for the project (n = 36),Footnote 2 and codifications of previous regulations (n = 9). Secondly, Commission officials, either senior policy officers or heads or deputy heads of units leading the remaining 64 legislative proposals, were formally invited to participate in the research project. Ultimately, the main analyses of this article rely on the data provided by 30 public officials leading 28Footnote 3 legislative proposals for which interviewees mentioned at least one interest group as a key actor when developing the legislative proposal and provided complete information about the interest groups mentioned.

As noted above, we focus our attention on groups that for some reason were considered prominent or ‘top-of-mind’ among public officials working on the different policy issues (Halpin & Fraussen, 2017). In order to identify prominent groups, we asked the public officials leading the 28 legislative proposals who were key actors when developing the policy under discussion. Importantly, while prominence (just like other concepts of policy engagement such as access) might be related to influence, this is not necessarily the case (see discussion in Fraussen et al., 2018). In total, public officials leading the 28 legislative proposals mentioned 103 interest groups as key actors. Some of these groups are mentioned by several public officials involved in different policy issues, in that respect, the number of unique groups in our data set is 75.Footnote 4

As we exclude groups that were not considered key actors by public officials, this study should be considered as a first 'plausibility probe' of the hypotheses laid down which will need further scrutiny among broader and more diverse samples of interest groups (King et al., 1994, p. 209).

Our operationalizations and analyses rely on three different data sources. Firstly, our dependent and explanatory variables are constructed through the responses provided by public officials during the interviews. Secondly, for each of the groups mentioned by public officials we hand coded group-level characteristics by retrieving information from their websites. Lastly, we conducted desk research using EU official documents and websites in order to collect issue-level information about the 28 legislative proposals included in the study. In addition, we make use of a fourth database to test the validity of our dependent variable, namely interviews with representatives of interest groups involved in the 28 policy issues.

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable (i.e., perceived influence) is measured with a question asked to public officials where they indicated to what extent the interest groups mentioned were decisive for the policy outcomes. That is, instead of assessing whether a particular demand of an interest group was incorporated in the final legislation, we want to know whether the voice of certain groups is perceived as more significant than others in shaping the policy outcomes (Halpin, 2014, p. 182; Maloney et al., 1994, p. 26).

The literature has highlighted different approaches to assess interest group influence, namely process tracing, the degree of preference attainment, and attributed influence (Dür, 2008). Here we take public officials’ perspective to assess the degree of influence they attribute to interest groups. Although it does not enable us to capture actual influence, this approach has important advantages. First, aligned with reputational power approach, this measure is supposed to be close to reality because ‘it relies on judgments of actors that are directly involved in the (…) decision-making process’ who have the ‘most accurate view of how power is allocated among actors’ (Fischer & Sciarini, 2015). Second, it allows to take into account various channels of influence, including behind-the-scene activities, and facilitates the assessment of influence of organized interests across a wide range of issues (rather than focusing on one specific policy process) and different phases of policymaking. In other words, our measure provides an encompassing view of influence as it 'allows to gauge the impact of such unobtrusive mechanisms and capture both formal and informal ways of influence' (Binderkrantz & Rasmussen, 2015; Flöthe, 2019, p. 172; Tallberg et al., 2018).

Perceived influence is measured with the following question: ‘to what extent were stakeholders mentioned decisive for the final policy outcome?’ The options were: 1 = Not at all; 2 = To some extent; 3 = To a large extent. On average, interest groups mentioned by public officials score 2.243 (SD = 0.585).

Even though the public officials interviewed were mostly active at the formative stage, their knowledge about the policy issue and about the positions and preferences of the actors involved ensures that their assessment of the dependent variable is accurate. Nonetheless, to assess the validity of this variable and address common source bias, we compare the responses of public officials with the one given by interest group representatives involved in the same set of regulations and directives.Footnote 5 In 31 out of 43 observations with available data from both public officials and interest groups, both public officials and interest group representatives assigned identical scores on the question about how decisive were the interest groups for the final policy outcome, confirming the validity of our dependent variable.Footnote 6

Explanatory and moderating factors

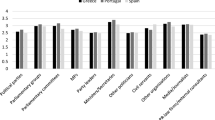

Our explanatory variables are constructed based on public officials' assessment of their interaction with those groups that they mentioned as being key for the development of a legislative proposal. More specifically, we rely on the question ‘why did you interact with this actor’. Respondents had to indicate whether each of the 9 items in Table 1 were applicable (1) or not (0) for the legislative proposal under scrutiny.

The items included in each of the three variables have been selected based on our conceptualization of the explanatory factors and confirmed with a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (see Table A1 in Appendix A). As reported in Table A1, 'policy expertise' relates to 'analytical capacities' as well as with the 'policy insiderness' factor. Additionally, the item 'for representing a key constituency' also relates to items in the 'analytical capacities' factor. Lastly, the item 'being a regular partner' included in the construct 'policy insiderness', also relates to 'political capacities'. Because some of the items relate to different dimensions, several robustness checks have been conducted to further validate the analyses (Appendix C).

The final variables are additive indexes that range from 0 to 3 for each of the three constructs. Interest groups score on average 1.514 (SD = 1.042) for analytical capacities, 1.202 (SD = 1.034) for political capacities, and 2.009 (SD = 0.986) for policy insiderness. Even though the three variables are significantly and positively correlated, the correlation coefficients between them are below 0.5 (see Table A2 in the Appendix).Footnote 7

In addition to these three core explanatory variables, we include a moderating factor: advocacy salience. We center on 'advocacy salience' as one of the dimensions related to salience that is distinct from 'media' and 'decision-makers' salience (Beyers et al., 2018). More precisely, this variable is measured by the number of stakeholders active on the issue through different consultation tools (Fraussen et al., 2020). This operationalization of salience based on the policy activity of lobbying actors has been used before (Bunea, 2013; Junk, 2019; Klüver, 2011). The fact that stakeholders mobilize on one of the consultation tools available at the EU level is a good indication that the policy matter is relevant and important for them. To obtain a complete list of groups involved in each of the legislations considered, we consulted the proposal of the European Commission, available consultation documents, and impact assessments. As we aimed to obtain as comprehensive a picture of stakeholder mobilization as possible, we also revised other official documents, such as EU websites and registries of expert groups. Furthermore, if the list of stakeholders participating in a particular type of consultation could not be identified via these publicly available sources, we contacted the responsible DG to request the list of stakeholders involved.Footnote 8 The final measure of advocacy salience is logged in the analysis due to a skewed distribution and transformed into a binary factor that distinguishes between issues with low advocacy salience from those with high advocacy salience.Footnote 9

Control variables

At the group-level, we control for group type by distinguishing between organizations that represent economic interest from citizen groups. There is significant debate in the field about whether group type matters for how influential they are (Dür et al., 2015; Klüver, 2013; Mahoney, 2008), yet the findings are not conclusive. We also control for whether interest groups have members—either individuals or organizations—or not (Albareda, 2021). This is an important distinction as membership-based interest groups are more likely to possess political capacities, whereas non-membership groups, such as firms usually possess expert knowledge (Bouwen, 2002).

Lastly, at the issue-level, we control for whether the regulation relates to an economic or a non-economic policy domain. Following the logic that context matters (Halpin, 2014, pp. 191–192) when studying interest groups’ policy capacities and their potential relevance for shaping policy outcomes, we distinguish policy issues developed under 'core' economic Directorate-Generals (DGs) of the Commission from those developed in non-economic DGs.Footnote 10 Here, we expect that this control variable might moderate the effect of analytical and political capacities on the dependent variable, as the former are presumably more relevant among economic policy domains, whereas the latter is more demanded in non-economic policy domains.

Table A2 in the Appendix B provides a summary of the descriptive statistics and the correlations coefficients among all the variables.

Examining perceived influence of interest groups

Before presenting the results of the multivariate analyses, we provide a description of our main variables. Regarding our dependent variable, 8% of identified interest groups were considered as 'not decisive at all by public officials', whereas 60% and 32% were considered as 'to some extent' and 'to a large extent' decisive respectively. This variation in the extent to which interest groups are perceived as influential by public officials indicates that the dependent variable (i.e., perceived influence) is empirically different from the sampling question (i.e., being a key actor). Regarding our main explanatory factors, their average scores show that public officials more frequently interact with policy insiders. This is followed by the possession of analytical capacities and, lastly, political capacities are the least frequently mentioned factor among public officials.Footnote 11 However, as shown in the correlation matrix (Table A2 in Appendix B), both analytical and political capacities are positively and significantly related to our dependent variable, whereas policy insiderness is not significantly related to the perceived influence of groups on policy outcomes.

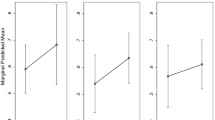

To test the six hypotheses, we conducted four mixed effects ordered logistic regressions, where interest groups are nested in policy issues. All models are multilevel models with random intercepts for policy issues to account for the heterogeneity of different policy issues (Gelman & Hill, 2007). The models have been built stepwise, whereas the tables presented below include the full models with all controls. The results presented below are confirmed with several robustness checks (i.e., controlling for organizational age, resources and issue-complexity; using alternative operationalizations of our explanatory factors; and employing a multilevel OLS, see robustness tests in Appendix C). Importantly, the Vif scores in the main models range from 1.135 to 1.482, indicating that multicollinearity is not a problem. Additionally, the proportional odds assumption test confirms that ordinal regressions are the best approach to analyze the data.Footnote 12 Last, all Models in Table 2 yield a significant improvement of the model fit when compared to their baseline models with only the control variables.

Model 1 tests hypotheses 1 and 2. We observe that H1a and H1b, based on the resource exchange approach, are confirmed. Groups that are seen as having more analytical and political capacities are perceived as more influential for final policy outcomes. Regarding H1a, public officials in the Commission need technical, detailed, and quality information about policy issues they are working on. In line with previous research, the possession of analytical capacities increases the policy impact of groups in decision-making processes (Dür et al., 2015; Flöthe, 2019; Tallberg et al., 2018). When testing H1b, we also find a positive and significant relationship between political capacities and the perceived influence of interest groups. Intriguingly, previous investigations exploring the effects of similar constructs, namely the possession of political information on lobbying success at the national (Flöthe, 2019) and international (Tallberg et al., 2018) level, do not find the same relationship. Yet, political capacity (measured in terms of citizen support) has been identified as a relevant factor affecting influence of interest groups in studies focusing on the interaction between groups and the European Commission (Klüver, 2011). Public officials of the Commission may be particularly attentive to groups with political capacities (more than public officials in other polities) due to the democratic deficit of EU institutions (Rittberger, 2005) and the need to legitimize policy choices to different audiences.

Contrary to our expectations, the extent to which groups are perceived as policy insiders by public officials does not affect their perceived influence on policy outcomes, hence H2 is rejected. Even though our descriptive statistics show that the degree of policy insiderness is the most important reason for being regarded as a key actor by public officials – which is aligned with previous research (see Braun, 2013) –, it does not matter when explaining perceived influence. That is, interest groups that establish a tight relationship with public officials, are not perceived as more influential on policy outcomes. Aligned with previous findings, this result ‘supports an optimistic view over the democratic credentials and legitimacy of the EU’ (Bunea, 2017; see also Quitkatt & Kotzian 2011), because the elitist tendencies derived from the power of policy insiders might be less severe than previously found (e.g., Coen, 2009).

Models 2 to 4 test the moderating effect that advocacy salience has on the relationship between our explanatory factors and interest groups' perceived influence (H3s). None of our policy capacity factors is significantly related to the dependent variable when controlling for the moderating effect of advocacy salience. However, we observe different trends. As expected, having analytical capacities is always important to be perceived as influential for policy outcomes (regardless of the levels of advocacy salience). As for the interaction with political capacities, the higher exposure of salient policy issues makes groups with political capacities more relevant, since public officials want to ensure that they accept the final policy outcomes. However, this effect is only significant (p-value = 0.095) when exclusively testing the interaction effect without the other (control) variables.

Regarding H3c, higher degrees of policy insiderness are positively and significantly related to perceived influence particularly in salient policy issues. This result indicates that public officials behave differently depending on issue salience and they perceive policy insiders as more influential when a large number of stakeholders are mobilized. In this situation, the problem for public officials is that there is an overload of attention and information. Consequently, in salient policy issues, public officials are more likely to rely on previous experiences, shortcuts, and heuristics when assessing which groups' policy input should be taken into account. In contrast, as shown by the negative and significant coefficient of the variable ‘policy insiderness’ in model 4, when advocacy salience is low, groups with high levels of policy insiderness are less likely to be perceived as influential. In other words, in quiet policy corners, policy insiders are seen as less relevant than groups that are not perceived as such. This puzzling finding (as well as the negative and significant coefficient for policy insiderness reported in model 3) might be due to our focus on regulatory issues where interest groups have good ‘opportunities for individual, direct access to decision-making institutions’ and thus ‘information from insiders becomes less relevant and valuable’ (Bunea et al., 2022).

The positive relationship between salience and policy insiderness on perceived influence is aligned with Jordan and Maloney’s (1997) discussion of policy communities. As they note, policy communities are means to make sense within modern policy making (Jordan & Maloney, 1997 see also, Jones & Baumgartner, 2012). That is, particularly in highly salient policy issues with significant outside pressure, policy is resolved in terms of pragmatism and based on trust relationships derived from previous interactions. Yet, as a consequence, public officials might fall into a confirmation bias trap and pay more attention to those groups that were valuable or trustworthy partners in previous policy processes. While this facilitates order and control over the policy process, it may hamper the ability to comprehensively tackle policy issues (Baumgartner & Jones, 2015, pp. 13–16). Importantly, all these results are confirmed after conducting several robustness checks (see Appendix C).

In terms of group- and issue-level control variables, only advocacy salience is significantly related to our dependent variable (see Model 4). The remaining control variables are not significantly related to perceived influence for the final policy outcome: economic groups are not perceived as being more or less influential for the final policy outcome when compared to citizen groups (for a discussion see, Dür et al., 2015). Likewise, representing members (either organizations or individuals) does not matter for perceived success, and neither does the substantive nature of the policy issue (economic versus non-economic).

Conclusions

This article examines why public officials identify some interest groups as more influential for policy outcomes of EU legislative proposals. In doing so, we make three important contributions to the literature. First, we assess the policy relevance of prominent interest groups by unpacking why some of them are perceived as more influential for policy outcomes among public officials. In doing so, we provide a novel contribution to the existing literature that analyzes the influence of interest groups (e.g., Binderkrantz et al., 2014; Dür et al., 2015; Heaney; Stevens & De Bruycker, 2020). Secondly, we advance our understanding of the dynamics behind interest group influence by going beyond exchange theory (e.g., Bouwen, 2002) and considering behavioral elements related to the routines and heuristics of public officials (Baumgartner & Jones, 2015; Braun, 2012, 2013; Simon, 1997), thus offering a more comprehensive understanding of the bases of power that enhance interest groups’ perceived influence. Thirdly, building upon previous research (Beyers et al., 2018; Stevens & De Bruycker, 2020; Willems, 2020), we clarify the moderating role of advocacy salience, a crucial contextual factor that alters the strategic and behavioral choices of public officials and shapes their interactions with interest groups.

Our empirical focus and design have implications for the interpretation and generalizability of our findings. First, our analysis is centered on EU legislative proposals with a regulatory component, which may affect how our results travel across other polities and legislative types. For instance, Commission officials are in high need of analytical and political capacities, two resources that may be less relevant for national governments or in the context of (re)distributive policy issues (Berkhout et al., 2017). Second, the data generation process is susceptible to measurement bias as it is based on a limited number of interviews with public officials, who are the key source of information for the main explanatory factors and the dependent variable. More specifically, the main dependent and independent variables of the study are based on perceptions of these public officials. As discussed, the low correlation between interest group economic resources (as reported in the Transparency Register) and our measures of policy capacities and insiderness illustrate the conceptual and empirical relevance of adding data based on perceptions. However, as acknowledged by reputations scholars, measurements of perceived influence (or power) have inherent limitations because of the multi-dimensionality of the concept, thus making it difficult to precisely assess on which specific criteria public officials based their assessment of influence (Fischer & Sciarini, 2015; James & Christopoulos, 2018). Future research would therefore benefit from complementing these reputational measures (which might also be subject to social desirability) with observational data. Third, our findings, in particular regarding policy insiderness, merit more research that examines the role of exchange and behavioral approaches with larger datasets and alternative research designs, such as (survey) experiments. Last, our empirical analyses have focused on prominent interest groups that are regarded as key players by public officials on the policy issue under discussion. While this represents a most likely case, this research has demonstrated that even within this set of key actors, some groups are considered as more influential than others by public officials, and more importantly, we have advanced our understanding of these differences and their potential drivers. Ideally, future research would apply and fine-tune this approach with larger and more diverse samples of interest groups, and a higher number of policy issues.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for the assessment of interest groups in policy-making processes. According to our results, EU public officials particularly value policy capacities because when groups are perceived as possessing analytical and political capacities, they are more likely to be seen as influential for final policy outcomes—thus confirming the importance of policy capacities in public policy processes (Daugbjerg, 2022; Daugbjerg et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2015). This is in line with expectations about the strategic choices of public officials derived from exchange theory and resonates with earlier interest group research (Bouwen, 2002, 2004; Braun, 2012; Flöthe, 2019). Regarding the effect of policy insiderness, our findings suggest that public officials are not necessarily biased in favor of the actors with whom they regularly meet. This is an important and positive normative finding because it shows that in regulatory issues, public officials are not necessarily captured by their set of regular partners, which reinforces the pluralist tendencies of the Commission (Quitkatt & Kotzian, 2011).

Intriguingly, the relevance of policy capacities for the perceived influence of interest groups is not contingent on the advocacy salience of legislative proposals. In other words, the possession of analytical and political capacities is always important for interest groups if they want to have policy impact on decision-making processes. More specifically, our results regarding analytical capacities confirm previous research (Albareda, 2020; De Bruycker, 2016), and highlights the importance of expertise within the Commission. Importantly, this finding might be a consequence of our empirical focus on the Commission, which as the institution responsible for developing legislative proposals is in high need of analytical capacities to make sure that the legislation is technically feasible in every EU member state (Klüver, 2011). Our findings regarding the importance of political capacities in highly salient issues point towards a similar direction as the results obtained by Willems (2020); i.e., advocacy salience makes political capacities more relevant. However, our results do not hold when adding the control variables and thus need to be further examined with larger data sets.

Finally, an important contribution of our study is that, in salient issues, greater degrees of policy insiderness are related to higher levels of perceived influence (Jordan & Maloney, 1997). This is a clear illustration of the role of public officials' heuristics and shortcuts when dealing with salient issues (Jones & Baumgartner, 2005). These shortcuts may ease the decision-making process, but can also hamper the democratic nature of the policy process as alternative views, perspectives, and voices might not be taken into account (see the trade-off between diversity and clarity described by Baumgartner & Jones, 2015, pp. 50–52). From a normative point of view, it is precisely in salient policy issues that public officials should combine information from different sources to gauge the magnitude of the problem and to design an appropriate response. However, EU public officials seem to fall into the ‘identification with the means’ phenomenon (Simon, 1997), which locks in previous ways of doing things, making the adoption of new or alternative policy solutions more difficult, and moving away from the status quo more challenging.

Notes

Research for this article has been embedded within a larger research project aimed at explaining stakeholder engagement in regulatory governance (see Braun et al., 2020).

To account for variation across policy areas (Van Ballaert, 2017), the policy issues included cover different policy areas where the EU has exclusive or shared competence with member states: (1) Finance, banking, pensions, securities, insurances; (2) State aids, commercial policies; (3) Health; (4) Sustainability, energy, environment; (5) Transport, telecommunications; (6) Agriculture and fisheries.

In one issue, the input provided by the leading public official was subsequently complemented with two interviewees also involved in the same dossier that provided information on three additional stakeholders that were involved in the process but not mentioned by the first interviewee.

On average, public officials involved in the 28 regulatory issues mentioned 3,68 interest groups (SD = 2.42; min. = 1, max. = 9).

All the interest groups mentioned by public officials were invited for an interview to discuss the policy issue in which they were mentioned. In total, 41 interviews were conducted with interest group representatives. In these interviews, interest group representatives were asked (1) which were according to them the "key" stakeholders involved in the policy issue and (2) "how decisive were key stakeholders involved in the policy issue under examination".

We do not observe any major disagreement among the twelve cases with different scores. In eleven cases where public official indicated that the actor was decisive either to some extent or to a large extent, interest groups never said that the actors was not at all decisive. In one observation public official considered an actor as not at all decisive, whereas the interest groups interviewed regarded the actor as 'to some extent' decisive. Interest group representatives assign higher levels of decisiveness to other interest groups (mean = 2.54, SD = 0.50; N = 43) when compared to public officials (mean = 2.35; SD = 0.52; N = 43). As a further test of the validity of the variable, we ran ICC test among the scores assigned by public officials and other stakeholders. The value is 0.56, indicating a fair/good reliability score (Hallgren, 2012).

We have explored the correlation values of the three main explanatory factors and the level of resources (i.e., FTEs) as reported in the Transparency Register. The correlation values are below 0.1 and in no case is the p-value significant. This highlights the empirical and conceptual distinction between perceived policy capacities and insiderness on the one hand, and the economic resources of interest groups on the other hand. As a consequence, our explanatory variables are based on public officials’ assumptions and general knowledge about interest groups’ policy capacities and insiderness.

By relying on an adapted version of the consultation tools listed by the European Commission Better Regulation Guidelines, we reviewed the following consultation tools: open/public (online) consultation; survey and questionnaire; stakeholder conference/public hearings/events; stakeholder meetings/workshops/seminars; focus groups; interviews; commission expert groups/similar entities; SME panels; consultations of local/regional authorities (networks of the Committee of the Regions); direct consultation of special stakeholder groups (including Member States); others. The reliability of this variable has been examined by conducting a correlation analysis with another variable related to salience, namely the number of newspaper articles published about the legislative proposal in the following outlets: Financial Times, Politico Europe, Agence Europe, EurActive, EUObserver, and European Voice (see Braun et al., 2020). Importantly, these variables are significantly correlated (p < 0.001) at 0.689.

The skewness of the raw variable is 1.04, which is aligned with previous research (Baumgartner et al., 2009). More specifically, on average policy issues attracted 98.38 stakeholders (SD = 108.114), with some issues having zero stakeholders involved through the consultations mechanisms considered and one issue that attracted 341 stakeholders.

The dichotomization of the logged variable is based on the quantile distribution of the logged variable (from 0 to 50% is categorized as "low" and from 51 to 100% as "high"), and is aimed at avoiding that few extreme observations drive the results of our models. However, our robustness section runs the models with this variable as a continuous (logged) factor and the results hold.

Regulations and directives have been coded as 1 when the DGs responsible was Competition, Economic and Financial Affairs, Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union, Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, or Taxation and Customs Union. Otherwise, the policy issues have been coded as 0 (Murdoch & Trondal, 2013, p. 7).

Based on a one-sample t-test comparing the means of each factor to the overall mean of the three factors, we find that policy insiderness has a significantly higher mean, while political capacities' mean is significantly lower. Analytical capacities, does not significantly deviate from the overall mean.

A nominal test to assess the proportional odds assumption leads to non-significant p-values (i.e., above 0.05), indicating that the proportional odds assumption is met. The only exception is the variable 'advocacy salience' in the model 3 of Table 2, which has a p-value = 0.048.

References

Albareda, A. (2018). Connecting society and policymakers? Conceptualizing and measuring the capacity of civil society organizations to act as transmission belts. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(6), 1216–1232.

Albareda, A. (2020). Prioritizing professionals? How the democratic and professionalized nature of interest groups shapes their degree of access to EU officials. European Political Science Review, 12(4), 485–501.

Albareda, A. (2021). Interest group membership and group dynamics. In P. Harris, A. Bitonti, C. S. Fleisher, & A. S. Binderkrantz (Eds.), The palgrave encyclopedia of interest groups, lobbying and public affairs. Palgrave Macmillan.

Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., & Leech, B. L. (2009). Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. University of Chicago Press.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (2015). The politics of information: Problem definition and the course of public policy in America. University of Chicago Press.

Berkhout, J., Hanegraaff, M., & Braun, C. (2017). Is the EU different? Comparing the diversity of national and EU-level systems of interest organisations. West European Politics, 40(5), 1109–1131.

Bernhagen, P., Dür, A., & Marshall, D. (2015). Information or context: What accounts for positional proximity between the European Commission and lobbyists? Journal of European Public Policy, 22(4), 570–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1008556

Beyers, J., Dür, A., & Wonka, A. (2018). The political salience of EU policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(11), 1726–1737. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1337213

Binderkrantz, A. S., Christiansen, P. M., & Pedersen, H. H. (2014). A privileged position? The influence of business interests in government consultations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(4), 879–896.

Binderkrantz, A. S., & Rasmussen, A. (2015). Comparing the domestic and the EU lobbying context: Perceived agenda-setting influence in the multi-level system of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(4), 552–569.

Bouwen, P. (2002). Corporate lobbying in the European Union: The logic of access. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760210138796

Bouwen, P. (2004). Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research, 43, 337–369.

Bouwen, P. (2009). The European Commission. In D. Coen & J. Richardson (Eds.), Lobbying the European Union: Institutions, actors and policy. Oxford University Press.

Braun, C. (2012). The captive or the broker? Explaining public agency-interest group interactions. Governance, 25(2), 291–314.

Braun, C. (2013). The driving forces of stability: Exploring the nature of long-term bureaucracy-interest group interactions. Administration & Society, 45(7), 809–836.

Braun, C., Albareda, A., Fraussen, B., & Müller, M. (2020). Bandwagons and quiet corners in regulatory governance. On regulation-specific and institutional drivers of stakeholder engagement. International Review of Public Policy, 2(2), 209–232.

Bunea, A. (2013). Issues, preferences and ties: Determinants of interest groups’ preference attainment in the EU environmental policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(4), 552–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.726467

Bunea, A. (2017). Designing stakeholder consultations: Reinforcing or alleviating bias in the European Union system of governance? European Journal of Political Research, 56, 46–69.

Bunea, A., Ibenskas, R., & Weiler, F. (2022). Interest group networks in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 61, 718–739.

Coen, D. (2009). Business lobbying in the European Union. In D. Coen & J. Richardson (Eds.), Lobbying the European Union: Institutions, actors and policy. Oxford University Press.

Commission, E. (2018). A comparative overview of public administration characteristics and performance in EU28. Publications Office of the European Union.

Daugbjerg, C. (2022). Against the odds: How policy capacity can compensate for weak instruments in promoting sustainable food. Policy Sciences, 2022, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11077-022-09466-2

Daugbjerg, C., Fraussen, B., & Halpin, D. R. (2018). Interest groups and policy capacity: Modes of engagement, policy goods and networks. In X. Wu, M. Howlett, & M. Ramesh (Eds.), Policy capacity and governance (pp. 243–261). Palgrave Macmillan.

De Bruycker, I. (2016). Pressure and expertise: Explaining the information supply of interest groups in EU legislative lobbying. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(3), 599–616.

Dür, A. (2008). Measuring interest group influence in the EU: A note on methodology. European Union Politics, 9(4), 559–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116508095151

Dür, A., Bernhagen, P., & Marshall, D. (2015). Interest group success in the European Union. Comparative Political Studies, 48(8), 951–983.

Eising, R. (2007). The access of business interests to EU institutions: Towards élite pluralism? Journal of European Public Policy, 14(3), 384–403.

Fischer, M., & Sciarini, P. (2015). Unpacking reputational power: Intended and unintended determinants of the assessment of actors’ power. Social Networks, 42, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCNET.2015.02.008

Flöthe, L. (2019). Technocratic or democratic interest representation? How different types of information affect lobbying success. Interest Groups and Advocacy, 8(2), 165–183.

Fraussen, B., Albareda, A., & Braun, C. (2020). Conceptualizing consultation approaches: Identifying combinations of consultation tools and analyzing their implications for stakeholder diversity. Policy Sciences, 53, 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09382-3

Fraussen, B., Beyers, J., & Donas, T. (2015). The Expanding core and varying degrees of insiderness: Institutionalised interest group access to advisory councils. Political Studies, 63(3), 569–588.

Fraussen, B., Graham, T., & Halpin, D. R. (2018). Assessing the prominence of interest groups in parliament: A supervised machine learning approach. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(4), 450–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2018.1540117

Fraussen, B., & Halpin, D. (2020). Interest Groups, the Bureaucracy, and Issue Prioritization. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

Gelman, A., & Hill, C. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press.

Grömping, M., & Halpin, D. R. (2021). Do think tanks generate media attention on issues they care about? Mediating internal expertise and prevailing governmental agendas. Policy Sciences, 54(4), 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11077-021-09434-2/FIGURES/3

Grossmann, M. (2012). The not-so-special interests: Interest groups, public representation and American governance. Standford University Press.

Hall, R. L., & Deardorff, A. V. (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 69–84.

Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023

Halpin, D. (2011). Explaining policy bandwagons: Organized interest mobilization and cascades of attention. Governance, 24(2), 205–230.

Halpin, D. R. (2014). The Organization of Political Interest Groups: Designing advocacy. Routledge.

Halpin, D. R., & Fraussen, B. (2017). Conceptualising the policy engagement of interest groups: Involvement, access and prominence. European Journal of Political Research, 56(3), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12194

Heaney, M. T. (2014). Multiplex networks and interest group influence reputation: An exponential random graph model. Social Networks, 36(1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCNET.2012.11.003

James, S., & Christopoulos, D. (2018). Reputational leadership and preference similarity: Explaining organisational collaboration in bank policy networks. European Journal of Political Research, 57(2), 518–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12237

Jones, B. D. (2003). Bounded rationality and political science: Lessons from public administration and public policy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(4), 395–412.

Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The Politics of Attention: How government prioritizes problems. University of Chicago Press.

Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2012). From there to here: Punctuated equilibrium to the general punctuation thesis to a theory of government information processing. Policy Studies Journal, 40(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00431.x

Jordan, G., & Maloney, W. A. (1997). Accounting for subgovernments: Explaining the persistence of policy communities. Administration & Society, 29(5), 557–583.

Junk, W. M. (2019). When diversity works: The effects of coalition composition on the success of lobbying coalitions. American Journal of Political Science, 63(3), 660–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12437

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton University Press.

Klüver, H. (2011). The contextual nature of lobbying: Explaining lobbying success in the European Union. European Union Politics, 12(4), 483–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511413163

Klüver, H. (2013). Lobbying in the European Union: Interest groups, lobbying coalitions, and policy change. Oxford University Press.

Klüver, H., Braun, C., & Beyers, J. (2015). Legislative lobbying in context: Towards a conceptual framework of interest group lobbying in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(4), 447–461.

Lodge, M. (2008). Regulation, the regulatory state and European politics. West European Politics, 31(1–2), 280–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380701835074

Lowery, D. (2013). Lobbying influence: Meaning, measurement and missing. Interest Groups & Advocacy, 2(1), 1–26.

Lowery, D., & Gray, V. (2004). A neopluralist perspective on research on organized interests. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290405700114

Mahoney, C. (2007). Lobbying Success in the United States and the European Union. Journal of Public Policy, 27(1), 25–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X07000608

Mahoney, C. (2008). Brussels versus the beltway: Advocacy in the United States and the European Union. Georgetown University Press.

Majone, G. (1999). The regulatory state and its legitimacy problems. West European Politics, 22(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389908425284

Maloney, W. A., Jordan, G., & McLaughlin, A. M. (1994). Interest groups and public policy: The insider/outsider model revisited. Journal of Public Policy, 14(1), 17–38.

McLaughlin, A. M., Jordan, G., & Maloney, W. A. (1993). Corporate lobbying in the european community. Journal of Common Market Studies, 31, 191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1993.tb00457.x

Murdoch, Z., & Trondal, J. (2013). Contracted government: Unveiling the European Commission’s Contracted Staff. West European Politics, 36(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.742734

Quittkat, C., & Kotzian, P. (2011). Lobbying via consultation: Territorial and functional interests in the Commission’s consultation regime. Journal of European Integration, 33(4), 401–418.

Rittberger, B. (2005). Building Europe’s parliament: Democratic representation beyond the nation-state. Oxford University Press.

Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci, 21, 129–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136406.

Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and Organizations. Sage Publications.

Simon, H. A. (1997). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organizations (Fourth). The Free Press.

Stevens, F., & De Bruycker, I. (2020). Influence, affluence and media salience: Economic resources and lobbying influence in the European Union. European Union Politics, 21(4), 728–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520944572

Tallberg, J., Dellmuth, L. M., Agné, H., & Duit, A. (2018). NGO influence in international organizations: Information, access and exchange. British Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 213–238.

Truman, D. B. (1951). The governmental process. Knopf.

European Union. (2012). Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Official Journal C 326, 26/10/2012 P. 0001 - 0390.

Van Ballaert, B. (2017). The European Commission’s use of consultation during policy formulation: The effects of policy characteristics. European Union Politics, 18(3), 406–423.

Versluis, E. (2019). The European regulatory state at risk?: The EU as a regulator of complex policy problems. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/spe.20160219ev

Weible, C. M., Heikkila, T., deLeon, P., & Sabatier, P. A. (2011). Understanding and influencing the policy process. Policy Sciences., 45(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11077-011-9143-5

Willems, E. (2020). Politicised policy access. Public Administration.

Wright, J. R. (1996). Interest groups and Congress: Lobbying, contributions, and influence. Pearson Education.

Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2015). Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy and Society, 34(3–4), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the journal editor, as well as the anonymous referees, for their valuable feedback and comments. We would also like to acknowledge participants at the 10th Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on the European Union. We acknowledge funding from the Dutch Research Council (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)), grant no. 452–14-012 (Vidi scheme).

Funding

Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)), grant 452–14‐012 (Vidi scheme).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albareda, A., Braun, C. & Fraussen, B. Explaining why public officials perceive interest groups as influential: on the role of policy capacities and policy insiderness. Policy Sci 56, 191–209 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-023-09491-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-023-09491-9