Abstract

This paper contributes to two recently identified gaps in policy design literature. First, an approach to measuring understudied specific on-the-ground measures, namely policy settings and calibrations, is developed, with particular attention to “calibration flexibility.” Second, with this better understanding of policy design, an emerging policy design causal mechanism perspective can be further elaborated upon. On-the-ground measures of the same policy instrument—Research of Excellence Centers programs are compared across six different countries. Introduced in many OECD countries in the 1990s, Centers of Excellence were implemented with the goal of reversing the trend of “brain drain” and retaining highly mobile scholars. A theory-building process tracing approach is adopted in order to identify first- and second-order mechanisms related to pursuit of the broad policy goals of retaining and attracting scientific talent along with improving research capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Public policy, by definition, represents a hypothesis that policy goals will be the outcome of implementing a set of policy instruments (Dewey 1927). Cashore and Howlett (2007), borrowing from Hall (1993) suggest a nuanced operationalization of public policy by distinguishing between the means and ends of policymaking as well as between abstract and concrete decisions. Their well-documented taxonomy framework (Table 1) distinguishes three orders of policy content at the high-level abstraction, program level, and on-the-ground (Howlett, 2009; Kern and Howlett, 2009).

Their taxonomy also differentiates policy ends or aims, (goals, objectives and settings) and their means (logic, policy instruments, and their calibrations) (Cashore & Howlett, 2007). By providing a nuanced approach to distinguishing between significant and minor policy change among six elements of policy regime, this two-dimensional framework overcomes the “dependent variable problem” commonly found in many policy studies assessing policy change (Cashore & Howlett, 2007).

In contrast to both policy instruments’ logic, which refers to norms that guide implementation preferences, the settings and calibration reflect the micro-level policy design of policy instrument (van Geet et al. 2021), both of which are understudied (Howlett and Ramesh 2022). Settings, the most concrete decision of policy ends, refer to the specific on-the-ground requirements of instruments, whereas calibration denotes the specific ways in which the instrument is used. Both are significant for at-least for three reasons. First, it allows opening the “black box” through which policy means, succeed or fail, to meet policy aims. Second, settings and calibrations are key to understanding the sources of inconsistencies in policy design, such as “providing simultaneous incentives and disincentives towards the attainment of stated goals” (Kern and Howlett, 2009, p. 6). Lastly, they are critical for maintaining policy congruence, namely the extent to which a consistent set of instruments supports a coherent set of goals (Strambo et al., 2015).

Recently, Capano and Howlett (2020) challenged the policy design scholarship to address a number of critical research gaps, two of which this study investigates. The first is the identification, selection, and use of policy settings and calibrations in an empirical case study. Second, by undertaking theory-building process tracing, we make an important theoretical contribution by arguing policy calibrations are critical activators of “first order” causal mechanisms that effect individual and group behavior. Moreover, second-order mechanisms that lead to long-term policy change such as the retention of scholars are also identified.

To address these conceptual challenges, we compare these on-the-ground measures common to the same policy instrument, Research-Excellence-Centers programs that are based throughout OECD countries. First developed in Canada nearly 25 years ago, networks of centers have since been developed with the broad goals of reversing “brain drain” trend, retaining highly mobile scholars, and improving a country’s overall scientific capacity across many fields (Aksnes et al., 2012; Auriol, 2007, 2010; Cervantes & Goldstein, 2006; Hunter et al., 2009; Giannoccolo, 2005; Levin & Stephan, 1999; Lundequist & Waxell, 2010; Malkamäki et al. 2001 Murakami, 2009; OECD, 2008, 2009; Porter, 1998; Power & Malmberg, 2008; Stephan, 2012; Thorn & Holm-Nielson, 2008).

In the following, we begin by reviewing policy calibration and settings literature and the recent theoretical developments to policy design mechanisms field. Next, the National Research-Excellence-Center programs as a policy instrument are introduced. The methods section specifies the selection process of the six case study countries (Canada, Denmark, Switzerland, German, Japan, and Israel), and the three step analytic procedure. From the analysis, we found that there are three-dimensional characteristics involved in specific on-the-ground measures of policy change, namely settings, calibration, and calibration flexibility. In addition, findings illuminate the role policy settings and calibrations play in the causal mechanisms understanding of policy design. Here, empirical evidence from the Research-Excellence-Center programs is used to develop generalizable process design causal mechanisms using theory-building process tracing.

Why settings and calibration of policy design matter?

As highlighted above in Table 1, policy design is comprised of six critical elements, which differ across two dimensions, namely policy focus and policy content. Specifically, policy focus distinguishes policy goals and means, whereas policy content distinguishes three levels of abstraction, namely high-level abstraction, program-level operationalization, and specific on-the-ground measures (Cashore & Howlett, 2007, see also Howlett, 2009; Kern and Howlett, 2009).

The essence of settings and calibrations, encompassing the specific on-the-ground measures, is adapting broad instruments, such as information, legislation, and incentives to specific situations, which is shaped by governance arrangements, policy regime characteristics, policy objectives, availability of resources and acceptability (Howlett, 2009, p. 82). This on-the-ground perspective captures the underlying policy changes that are often overlooked following current tendency to focus on the high-level abstraction and/or program-level operationalization (Howlett, 2009). Settings and calibrations are not only shaped by ideas and institutions. Rather, as we argue, they facilitate the adjustment of instruments to emerging social demands and to technical requirements. Nevertheless, little is known about how policy settings and calibration are used, although incorporated in Cashore and Howlett’s (2007) framework. It is now well-accepted that policy settings and their calibrations plays a key role “the specific ways within which policy instruments are used in order to attain policy targets” (Howlett, 2009, p. 75). Moreover, if not properly calibrated to the context, policy tools designed to alter the behavior of a target group might not work as intended (Oliver 2015). The policy design literature portrays the setting and calibration as policy regime elements that relates to the actual usage of instruments in practice, therefore considered to bridge design and implementation (Tosun & Treib, 2018). Furthermore, understanding settings and calibrations during design is required in order to assure congruence between goals and means (Howlett, 2009), which accords the well-established notion that policy actors do not simply import a program for implementation but, instead, adapt, fine-tune and customize it for their own uses (Bardach 2004).

There have been provisional insights of the kinds of settings and calibrations which might be put into place (Howlett and Ramesh 2022). Specifically, Linder and Peters (1989) identified eight attributes of instruments which were argued to affect specific “micro” tool calibration choices, including complexity of operation, level of public visibility, adaptability across uses, intrusiveness level, relative costliness, reliance on markets, chances of failure, and precision of targeting (p.56). More recently, Howlett (2019) draws on Salamon (2002) and specifies four criteria according to which calibration should be exercised in order to meet the settings: coerciveness degree required to accomplish the goal, whether delivery is direct or indirect, usage of preexisting implementation structures or creation of new ones and visibility in both policy review activities and budgeting. In the advocacy coalition framework (AFC), settings are referred to as secondary aspects of policy beliefs that represent a multitude of instrumental decisions and information searches necessary to implement the policy core in the specific policy area and are concerned with changes to administrative rules, budgetary allocations, disposition of cases, statutory interpretation and revisions as well as involving information regarding program performance (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993). Despite the explicit significance ascribed to secondary aspects, there has been very little follow-up ACF scholarship on secondary aspects. In a similar manner, Cole (2014) described settings and calibrations present properties in Ostrom’s IAD framework and specifically the rule types (e.g., choice and information) and how they are articulated (acceptability of actions, information flows).

Policy settings and calibrations have also been acknowledged in a limited number of empirical case studies, which further demonstrate the critical role that it plays in understanding policy success, for example, in environmental policies (Skogstad, 2020). Martens et al (2015) identify calibrations and settings in the governance-driven engagement policy engagement in two Canadian provinces (Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan). Wellstead and Howlett (2017) empirically assessed assisted tree migration policy calibrations in the Canadian and US forestry sectors. Barnett et al. (2020) found that changes to the policy settings and calibrations were critical to smart layering in Wisconsin’s forestry bioenergy sector. Howlett and Ramesh (2022) argue that the adjustment of specifications and calibrations has had a cumulative impact on expanding access to South Korea’s health care system. Despite these notable contributions, this area of policy design is routinely overlooked. For example, in an extensive review of environmental policy instruments, Pacheco-Vega (2020) only sparingly discussed policy settings and calibrations.

First- and second-order policy design mechanisms

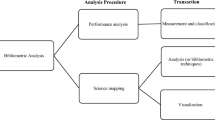

Recently, there has been a growing interest in policy-related causal mechanisms (Capano et al., 2019; van der Heijden 2021; Nullmeir and Kulmann 2022). Employing a causal mechanisms approach contributes to the policy design literature because the policy elements are typically descriptively described (Bouma et al., 2019). Causal mechanisms are generally referred to as an empirically traceable process that acts as a cause in generating the outcome (Mahoney, 2001). In the area of policy design, Howlett (2019) argued that meso-level policy instruments activate mechanisms leading to behavioral changes. In a similar manner, Capano et al (2019) and Capano and Howlett (2021) recently introduced a framework (Fig. 1) to clarify a mechanism-based approach to policy design. Central to this approach are first- and second-order mechanisms. First-order mechanisms are triggered by the tool’s application of state resources in order to affect the behavior of individuals, groups and structures. Typically, activators that trigger policy design mechanisms are policy calibrations and setting through which decision-makers set up their policy instruments and tool to influence group behavior and ultimately new outcomes (situation t1) (Capano & Howlett, 2021). A new outcome often influences second-order mechanisms. Examples include policy learning, diffusion, policy layering, and civic engagement. Through the calibration process policy-makers attempt to address the behavior of the target population by adjusting instruments. Importantly, tools can be calibrated at different levels of intensity, affecting the degree or speed to which a mechanism is activated (Barnett et al. 2020). With the empirical evidence known, we employ what Beach and Petersen (2019) refer to as theory-building process tracing in order to develop first- and second-order theorized causal mechanisms that are generalizable. This approach assists in helping unearth a plausible mechanism(s) from the National Research Center of Excellence program cases that, with some level of confidence, is considered to be responsible for producing the observed outcomes (Gerring 2008). Employing what Beach and Petersen (2019) refer to as “minimalist process tracing” contributes to Capano et al.’s (2019) framework by arguing that it is the settings, calibrations, and their flexibility embedded with policy instruments are the activators of the causal mechanisms leading to individual and group behaviors.

Adapted from Capano and Howlett (2021)

The mechanistic process from a policy design perspective.

The policy instruments: Research Centers of Excellence programs

With a broad goal of strengthening academic research in an institutionalized and sustainable manner as well as offsetting “brain-drain,” a number of countries have established and funded Research Centers of Excellence programs (Malkamäki et al., 2001; Power & Malmberg, 2008). Their global spread has been portrayed as a “relatively stable (or constantly fashionable) trend” (Power & Malmberg, 2008, p. 235). These programs are intended to create international-level research environments, attract leading scholars, and are typically hosted by higher education institutions. Following their initial selection through a highly competitive process, the successfully chosen centers are provided with generous long-term resources. Further, these centers are meant to reflect the broader priorities and scientific interests of the researchers in that country—as opposed to so-called “strategic research centers” often established for a pre-defined cause. We elaborate on this below. Nearly all countries have sponsored subsequent rounds of program renewal, periodically (5–10 years) issuing requests for proposals.Footnote 1 Throughout a program’s lifespan, existing centers often compete for additional funding. Table 2 provides an overview of six examples of national center of excellent programs, all of which were part of our study and analysis below.

Data and methods

Initially, we reviewed 15 country calls for proposals for Research-Excellence-Center programs between 1989 and 2013 from which six were selected (Canada, Denmark, Switzerland, Germany, Japan, and Israel). The rationale for selection was that all six countries specifically experienced particular high levels of “brain drain” (Franzoni et al., 2012, see also IIE 2011). These six countries provide a useful long-term perspective regarding the durability of policy calibrations. The first call of proposals for Research-Excellence-Centers was initiated and subsequently adopted by Canada in 1989 followed by Denmark (1991) Switzerland (2001), Germany (2006), Japan (2007), and Israel (2011), a late adopter. Data were collected from two sources: formal policy documents and structured key informant telephone or face-to-face interviews (30–60 min) with Research-Excellence-Centers senior administrators. Policy documents, mainly the calls for the submission of competing proposals for the development of the centers, were analyzed to sketch the design of each of the centers. From this qualitative analysis, settings and calibrations, specified in Table 3, were developed and analyzed.

The policy design of the six National Center of Excellence programs was compared especially with regard to settings and calibrations. The analysis included three steps. First, the content of the policy settings was inductively identified from key informant interviews and the coding of policy documents–primarily the instructions for proposals and guidelines for the center’s operation. Second, three major settings were identified: budgetary funding, academic standards, and organizational features (see Table 4). For each of the settings, corresponding mechanisms were identified. A total of eight settings emerged; two for budgetary funding; three for academic standards; and three for organizational features (listed in Table 4). Third, for each country, the calibrations for each of the settings were inductively identified (see Table 5). To allow a comprehensive analysis, the calibrations of the different National Centers of Excellence programs were assessed and compared.

Unpacking the settings, calibrations, and calibration flexibility lends itself to a broader understanding of causal-oriented policy design. The inductive approach taken in the theory-building process tracing approach relied on the interviews, primary documents, and consulting the social sciences literature for causal mechanisms. Unlike statistical analysis, mechanisms are portable concepts that are often found in different contexts (Falleti & Lynch, 2009).

Findings: measuring on-the-ground policy design and identifying policy causal mechanisms

Comparing on-the-ground measures of the same policy instrument highlights two overlooked features of policy design. First, settings, defined here as the processes that expected to generate the on-the-ground policy outcomes. Second, calibration, defined here as the extent to which implementers are provided with discretion to adapt, fine-tune and customize the policy instrument. In the following, Table 4 specifies the three policy settings identified as well as their calibrations, and Table 5 specifies the calibration flexibility of the settings. When assessing the calibration for each setting, three levels of calibration flexibility, scored as low (1), medium (2) or high (3) were identified. The calibration flexibility of each of the eight settings’ in the six centers is specified in Tables 6, 7 and 8. Lastly, Table 9 shows the aggregate scores of calibration flexibility of the six National Center of Excellence programs.

Calibration flexibility in the budgetary settings

The flexibility of the two budgetary settings, budgetary framework and specific budgetary clauses was mixed. Despite the 17-year span between the development of Canada’s Excellence-Centers and Germany’s Excellence-Centers, both settings presented medium scores, (Table 6). Denmark and Switzerland presented fewer budgetary requirements and therefore presented medium to high scores. In contrast, Japan and Israel presented the least amount of calibration flexibility with low scores for both calibrations.

Calibration flexibility in the academic budgetary settings

The three academic budgetary settings were defined by the scientific research field, recruitment of new scholars, and doctoral studies requirements (Table 6). Canada and Denmark presented high flexibility scores across all three settings, namely not restricting the fields or intake of new scholars, and no doctoral requirements. The scores derived from the four other countries presented mixed results. Only Germany presented a high degree of flexibility in the scientific research field. It presented a medium degree of flexibility in terms of the recruitment of new scholars via incentives but presented very strict requirements for doctoral students. In the case of Switzerland, there were low scores regarding scientific fields permitted and the doctoral requirements. Japan and Israel’s calibration flexibility were split. Japanese NCEs enabled submission of proposals in research fields with potential for applicable research (medium flexibility), whereas in Israel, there was a defined process of field selection involving the cooperation leaders from scientific institutions who preceded over the call for proposals (medium flexibility). Both Japan and Israel required the recruitment of new scholars and gave specific instruction regarding the minimum number of scholars that the centers would be required but in contrast, these countries had no limitations on doctoral studies requirements.

Calibration flexibility in the organizational feature’s settings

The final set of calibration scores focused on the organizational features settings, namely the restriction regarding the years of operation, partnership requirements, and infrastructural equipment requirements (Table 8). Overall, there was greater overall flexibility compared to the three other settings. Only Israel presented a low flexibility across all three settings. In the remaining five countries, at least one low flexibility score. In Canada, Switzerland, and Germany, there were a number of criteria for the inclusion of partners. Conversely, these countries plus Japan had no restrictions on the longevity of Excellence-Centers national centers—that is they could operate indefinitely. With the exception of Japan, all had no restrictions in terms of allowances for infrastructure and equipment requirements.

Comparing aggregate calibration flexibility

Findings in Tables 6, 7 and 8 measured the tool’s calibration but were as measured in terms of its output, that is, policy intensity (Schaffrin et al. 2015). In Table 9, the aggregate scores from Tables 6, 7 and 8 are presented. Analysis of the six cases indicates that there emerged a clear trend of decreased calibration flexibility when comparing the early adopting countries such as Canada and Denmark compared to Israel, a late comer. The calibration flexibility scores are similar in Switzerland, Germany, and Japan, countries that followed a decade later. However, with the small N of cases, we are cautious about making a clear boundary between calibration scores of the leader, follower and laggard countries. A major implication is that by considering the calibration flexibility across a number of settings, there was a lumpiness in terms of the extent of that flexibility. That is, there were often cases in some countries where there was calibration inflexibility within some of the settings.

A policy design mechanism approach to national centers of excellence policymaking

In Table 10 and Fig. 2, we identify the first-order and second-order mechanisms that contribute to individual and group behavior, and ultimately to the retention of scientific talent and increased research capacity. Critical to theory-building process tracing is identifying the first-order and second-order mechanisms, both of which are abstract portable concepts that can readily be derived from the social sciences literature (Falleti 2006; Falleti & Lynch, 2009). In the case of the first order mechanisms, Un and Montoro‐Sanchez’s (2010) work informed our choice of entrepreneurial mobilization. Resource mobilization mechanisms (Desa 2012) and competition mechanisms (Mayntz, 2004) were also critical in the creation of national centers of excellence. Knowledge mobilization and transfer mechanisms were found to be critical and were developed in previous studies (Albrecht and Ziderman 1992; Nokes, 2009; Falch and Oosterbeek 2011; Shields & Evans, 2012). We also found the presence of technology transfer mechanisms to be critical (Harmon et al., 1997). Similarly, the presence of second-order mechanisms such as the diffusion of knowledge (Sorenson & Fleming, 2004), constituency building (Hirota & Jacobowitz, 2007), policy layering (Falleti & Lynch, 2009; Capano et al., 2019; van der Heijden et al. 2021), and policy reframing (Aukes et al., 2018) was present, all of which have been developed in previous social science research.

Discussion and conclusion

Drawing on a single policy instrument, namely National Centers of Excellence programs, two important contributions are made to the policy design literature. Previous scholarship, most notably by Ostrom (2019), Linder and Peters (1989), as well as Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993), have stressed the importance of this on-the-ground level of inquiry. However, on-the-ground aspects of policies has only received a passing recognition in the public policy scholarship. By introducing calibration flexibility, this study allows a more nuanced understanding of policy calibrations and settings. Notably, calibration flexibility is relevant for additional lines of future research. For example, calibration flexibility can be useful for implementation studies, which refer to the tension between discretion-as-granted and discretion as practiced (Hill & Hupe, 2002). Specifically, higher calibration flexibility reflects a higher level of discretion-as-granted to implementing agents and is expected to decrease the emergence of implementation gaps because they are provided with means to adapt formal directives to local context and circumstances. In a similar manner, public management studies stress the adaptation role of public managers (e.g., Gassner & Gofen, 2018; Gassner et al., 2022), and calibration flexibility allows to signal the extent to which implementation actors are provided with discretion in adapting policy instruments to specific contexts through calibration of policy instruments.

Finally, in line with the inroads made by recent scholarship on the role of policy-based causal mechanisms, this study identified policy design mechanisms specific to one policy instrument. Calibrations and settings play an important role as policy instrument activators. While beyond the scope of this paper, future research should determine how these mechanisms contributed to the outcomes, for example, the level of researcher retention and research output. Researcher could also use the measurement of calibration and settings as suggested here and examine calibration flexibility for additional policy instruments. Future research should shift from inductive theory-building process tracing to theory-testing process tracing. This would require unpacking mechanisms and finding a fit between the evidence and the theoretical assumptions (Ulriksen & Dadalauri, 2016). By drawing on this approach to process tracing Bayesian formalization can be applied (Paz & Fontaine, 2018). These potential research directions suggest consid

erable promise for a better understanding of policy design.

Notes

Canada and Denmark have initiated more than one round, and Israel supported two competitive processes for the establishment of Excellence-Centers.

References

Aksnes, D., Benner, M., Borlaug, S.B., Hansen, H.F., Kallerud, E., Kristiansen, E., Langfeldt, L., Pelkonen, A., & Sivertsen, G. (2012). Centres of excellence in the Nordic countries; A comparative study of research excellence policy and excellence centres schemes in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden, Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU), Working Paper 4/2012.

Albrecht, D., & Ziderman, A. (1992). Funding mechanisms for higher education: Financing for stability, efficiency, and responsiveness. World Bank Discussion Papers. World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433.

Aukes, E., Lulofs, K., & Bressers, H. (2018). Framing mechanisms: The interpretive policy entrepreneur’s toolbox. Critical Policy Studies, 12(4), 406–427.

Auriol, L. (2007). Labour market characteristics and international mobility of doctorate holders: results for seven countries, OECD science, technology and industry working papers 2007/2. OECD Publishing.

Auriol, L. (2010). Careers of Doctorate holders: Employment and mobility patterns, OECD STI Working paper 2010/4.

Bardach, E. (2004). The extrapolation problem: How can we learn from the experience of others?. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(2), 205–220.

Barnett, B., Wellstead, A. M., & Howlett, M. (2020). The evolution of Wisconsin’s woody biofuel policy: Policy layering and dismantling through dilution. Energy Research & Social Science, 67, 101514.

Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2019). Process-tracing methods: Foundations and guidelines. University of Michigan Press.

Bouma, J. A., Verbraak, M., Dietz, F., & Brouwer, R. (2019). Policy mix: Mess or merit? Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy, 8(1), 32–47.

Capano, G., Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Virani, A. eds., (2019). Making policies work: First-and second-order mechanisms in policy design. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2020). The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: Policy tools and the current research agenda on policy mixes. SAGE Open, 10(1), 2158244019900568.

Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2021). Causal logics and mechanisms in policy design: How and why adopting a mechanistic perspective can improve policy design. Public Policy and Administration, 36(2), 141–162.

Cashore, B., & Howlett, M. (2007). Punctuating which equilibrium? Understanding thermostatic policy dynamics in pacific northwest forestry. American Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 532–551.

Cervantes, M., & Goldstein, A. (2006). International mobility of talent: The challenge for Europe, Science and Technology for Development Conference, Maastricht, March 7–8.

Cole, D.H. (2014). Formal institutions and the IAD framework: Bringing the law back in. Available at SSRN 2471040.

Desa, G. (2012). Resource mobilization in international social entrepreneurship: Bricolage as a mechanism of institutional transformation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 727–751.

Falch, T. and Oosterbeek, H. (2011). Financing lifelong learning: Funding mechanisms in education and training.

Falleti, T. G. (2006). Theory-guided process-tracing in comparative politics: Something old, something new. Newsletter of the Organized Section in Comparative Politics of the American Political Science Association, 17(1), 9–14.

Falleti, T. G., & Lynch, J. F. (2009). Context and causal mechanisms in political analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 42(9), 1143–1166.

Franzoni, C., Scellato, G., & Stephan, P. (2012). Foreign born scientists: Mobility patterns for sixteen countries, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gassner, D., & Gofen, A. (2018). Street-level management: A clientele-agent perspective on implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(4), 551–568.

Gassner, D., Gofen, A., & Raaphorst, N. (2022). Performance management from the bottom up. Public Management Review, 24(1), 106–123.

Gerring, J. (2008). The mechanismic worldview: Thinking inside the box. British journal of political science, 38(1), 161–179.

Giannoccolo, P. (2005). Brain drain competition policies in Europe: A survey, Working Papers 534, Dipartimento Scienze Economiche, Universita' di Bologna.

Hall, P.A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, pp.275–296.

Harmon, B., Ardishvili, A., Cardozo, R., Elder, T., Leuthold, J., Parshall, J., Raghian, M., & Smith, D. (1997). Mapping the university technology transfer process. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(6), 423–434.

Hill, M., & Hupe, P. (2002). Implementing public policy: Governance in theory and in practice. Sage.

Hirota, J., & Jacobowitz, R. (2007). Constituency building and policy work: Three paradigms. The Evaluation Exchange, 13(1), 26–27.

Howlett, M. (2009). Governance modes, policy regimes and operational plans: A multi-level nested model of policy instrument choice and policy design. Policy Sciences, 42, 73–89.

Howlett, M. (2019). Procedural policy tools and the temporal dimensions of policy design. Resilience, robustness and the sequencing of policy mixes. International Review of Public Policy, 1(1:1), 27–45.

Howlett, M. & Ramesh, M. (2022). Designing for adaptation: static and dynamic robustness in policy-making. Public Administration.

Hunter, R. S., Oswald, A. J., & Charlton, B. (2009). The elite brain drain. Economic Journal, 119, 231–251.

IIE (Institute of International Education) (2011). Top 25 places of origin of international scholars, 2009/10–2010/11." Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange. Retrieved 18 Dec 2012 from http://www.iie.org/opendoors

Levin, S., & Stephan, P. (1999). Are the foreign born a source of strength for U.S. science? Science, 285, 1213–1214.

Linder, S.H. and Peters, B.G., 1989. Instruments of government: Perceptions and contexts. Journal of public policy, 9(1), 35–58.

Lundequist, P., & Waxell, A. (2010). Regionalizing “Mode 2”? The adoption of centers of excellence in Swedish research policy. Geografiska Annaler: Series b, Human Geography, 92(3), 263–279.

Mahoney, J. (2001). Beyond correlational analysis: Recent innovations in theory and method. In Sociological forum (pp. 575–593). Eastern Sociological Society.

Malkamäki, U., Aarnio, T., Lehvo, A., & Pauli, A. (2001). Centre of excellence policies in research: Aims and practices in 17 countries and regions, Publications of the Academy of Finland 2/01.

Martens, L., McNutt, K., & Rayner, J. (2015). Power to the people? The impacts and outcomes of energy consultations in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 1.

Mayntz, R. (2004). Mechanisms in the analysis of social macro-phenomena. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 34(2), 237–259.

Murakami, Y. (2009). Incentives for international migration of scientists and engineers to Japan. International Migration, 47(4), 67–91.

Nokes, T. J. (2009). Mechanisms of knowledge transfer. Thinking & Reasoning, 15(1), 1–36.

Nullmeier, F., & Kuhlmann, J. (2022). Introduction: A mechanism-based approach to social policy research. In: Causal mechanisms in the global development of social policies (pp. 3–29). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

OECD. (2008). The global competition for talent: Mobility of the highly skilled. OECD.

OECD. (2009). Policy brief, the global competition for talent. OECD.

Oliver, A. (2015). Nudging, shoving, and budging: Behavioural economic‐informed policy. Public Administration, 93(3), 700–714.

Ostrom, E. (2019). Institutional rational choice: An assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework. In Theories of the policy process (pp. 21–64). Routledge.

Pacheco-Vega, R. (2020). Environmental regulation, governance, and policy instruments, 20 years after the stick, carrot, and sermon typology. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(5), 620–635.

Paz, B., & Fontaine, G. (2018). A causal mechanism of policy innovation. The reform of Colombia’s oil-rents management system. Revista De Estudios Sociales, 63, 02–19.

Porter, M. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76, 77–90.

Power, D., & Malmberg, A. (2008). The contribution of universities to innovation and economic development: In what sense a regional problem? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 1, 233–245.

Sabatier, Paul A., Hank C., & Jenkins-Smith (Eds) (1993). Policy change and learning: An advocacy coalition approach. Westview press.

Salamon, L.M. (Ed) (2002). The tools of government: A guide to the new governance, Oxford University Press.

Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S. and Seubert, S. (2015). Toward a comparative measure of climate policy output. Policy Studies Journal, 43(2), 257–282.

Shields, J., & Evans, B. (2012). Building a policy-oriented research partnership for Knowledge Mobilization and Knowledge Transfer: The case of the Canadian Metropolis Project. Administrative Sciences, 2(4), 250–272.

Skogstad, G. (2020). Mixed feedback dynamics and the USA renewable fuel standard: The roles of policy design and administrative agency. Policy Sciences, pp.1–21.

Sorenson, O., & Fleming, L. (2004). Science and the diffusion of knowledge. Research Policy, 33(10), 1615–1634.

Stephan, P. (2012). How economics shapes science. Harvard University Press.

Strambo, C., Nilsson, M., & Månsson, A. (2015). Coherent or inconsistent? Assessing energy security and climate policy interaction within the European Union. Energy Research & Social Science, 8, 1–12.

Thorn, K., & Holm-Nielson, L. B. (2008). International mobility of researchers and scientists: Policy options for turning a drain into a gain. In A. Solimano (Ed.), The International mobility of Talent: Types, causes and development impacts. Oxford University Press.

Tosun, J., & Treib, O. (2018). Linking policy design and implementation styles. Routledge handbook of policy design, pp.316–330.

Ulriksen, M. S., & Dadalauri, N. (2016). Single case studies and theory-testing: The knots and dots of the process-tracing method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(2), 223–239.

Un, C. A., & Montoro-Sanchez, A. (2010). Innovative capability development for entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. Journal of Organizational Change Management., 23, 413.

van Geet, M.T., Verweij, S., Busscher, T. & Arts, J. (2021). The importance of policy design fit for effectiveness: a qualitative comparative analysis of policy integration in regional transport planning. Policy Sciences, 54(3), 629–662.

van der Heijden, J., Kuhlmann, J., Lindquist, E., & Wellstead, A. (2021). Have policy process scholars embraced causal mechanisms? A review of five popular frameworks. Public Policy and Administration, 36(2), 163–186.

Wellstead, A., & Howlett, M. (2017). Assisted tree migration in North America: Policy legacies, enhanced forest policy integration and climate change adaptation. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 32(6), 535–543.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gofen, A., Wellstead, A.M. & Tal, N. Devil in the details? Policy settings and calibrations of national excellence-centers. Policy Sci 56, 301–323 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-023-09496-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-023-09496-4